Explore the collection

Showing 8 items in the collection

8 items

Book

Rethinking China's Democracy Movement

Author Hu Ping was involved in the Xidan Democracy Wall movement in the late 1970s and now lives in the United States.

He has successively chaired the pro-democracy publications <i>China Spring</i> and <i>Beijing Spring</i>. This book, published in 1992, analyzes the reasons for the failure of the June Fourth Movement and summarizes the lessons learned. The last two chapters suggest how to continue the pro-democracy movement in the future.

Book

The Herald of History: The Solemn Promise of Half a Century Ago

Compiled by the Sichuan writer Xiao Shu (b. 1962), this book offers a variety of pro-democracy statements released by the Chinese Communist Party media, including short commentaries, speeches, editorials, and documents from <i>Xinhua Daily, Jiefang Daily, Party History Bulletin</i>, and <i>People's Daily</i> from 1941 to 1946. The essays criticize the Kuomintang government for running a "one-party dictatorship" and promised freedom, democracy and human rights.

The book was published by Shantou University Press in 1999. <a href="https://archive.ph/20220329191611/https://www.rfi.fr/tw/%E4%B8%AD%E5%9C%8B/20130817-%E9%A6%99%E6%B8%AF%E5%A4%A7%E5%AD%B8%E5%86%8D%E7%89%88%E3%80%8A%E6%AD%B7%E5%8F%B2%E7%9A%84%E5%85%88%E8%81%B2%E3%80%8B">According to Xiao Shu</a>, the book was heavily criticized by the then-head of the Propaganda Department, Ding Guangen. The publishing house was temporarily suspended, and copies of the book were destroyed. It was republished in Hong Kong by the Bosi Publishing Group in 2002, and reprinted by the Journalism and Media Studies Center of the University of Hong Kong in 2013.

图书

The Truth about Liu Wencai

In the mid-20th century, Liu Wencai, a large landowner in Sichuan Province, spent almost all of his family's wealth in his later years on promoting education, bridge construction and road building, and was known as a great benefactor in the region. However, during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, he was portrayed as an archetype of evil landlords in the 3,000-year history of feudalism in China.

As the controller of great wealth in southern Sichuan during the Republic of China period, Liu Wencai did accumulate a huge fortune from plunder in his early years, but in his later years he invested most of it in public welfare. He financed and presided over the construction of a highway, as well as the Wanchengyan irrigation system, benefiting hundreds of thousands of farmers. He also spent almost all of his family's wealth to found the Wencai Middle School (today's Anren Middle School), which at the time was known as Sichuan's best privately-run school. In the memories of the local people, Liu Wencai collected less land rent than what was collected by the government after 1949. He was praised for providing financial assistance to poor families during special days and festivals, and for mediating civil disputes in a fair manner.

These facts were erased under the ultra-leftist propaganda. The authorities even fabricated the story of Liu Wencai keeping farmers in a dungeon filled with water, as well as making sculptures depicting how Liu Wencai was exploiting farmers, in order to incite hatred against him. This made Liu Wencai one of the most famous evil landlords in China.

Periodicals

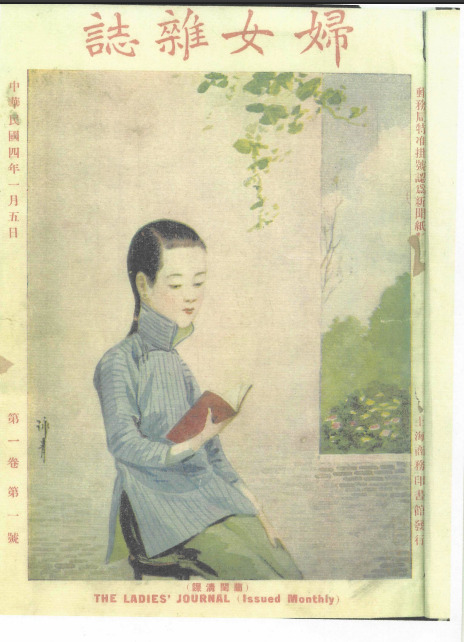

The Ladies Journal

The Ladies Journal was founded in January 1915 by the Commercial Press Shanghai. It was a monthly magazine primarily targeting upper-class women. It ceased publication in 1932 when the Commercial Press was destroyed by Japanese bombing. The magazine was distributed in major cities in China and overseas, such as Singapore. The magazine was considered an influential forum for the dissemination of feminist discourse in modern China, given its long operation and large readership.

The magazine spanned important historical periods such as the May Fourth Movement and the National Revolutionary period, and readers can see how the political environment and social trends influenced the political stance and style of the publication.

Although it was a women's magazine, the chief editors and the authors of most of the articles were men. According to Wang Zheng, Professor Emeritus of Women's and Gender Studies and History at the University of Michigan, the early articles of The Ladies Journal were more conservative. Although it advocated for women’s education, the goal was to train women to be good wives and mothers. Later, under the influence of New Culture Movement and the May Fourth Student Movement, the magazine was forced to reform itself and began to publish debates on women's emancipation as well as to call for more women's contributions, spread liberal feminist ideas, and support women's movements across the country.

1923 saw the beginning of the National Revolutionary period, and the Chinese Communist Party’s nationalist-Marxist discourse on women’s emancipation started to challenge liberal feminism, and the magazine's influence waned. In September 1925, the magazine ceased to be a cutting edge feminist publication after it changed its chief editor again and shifted its focus to ideas more easily accepted by conservative-minded readers,such as women's artistic tastes.

Although the <i>The Ladies Journal</i> was run by men, and some articles displayed contempt for and discrimination against women, it pointed out and discussed many issues that hindered women's social progress, such as lack of education, employment, economic independence, marriage freedom, sexual freedom, family reform, emancipation of slave girls, abolition of the child bride system, abolition of prostitution, and contraceptive birth control. It was also open to many different ideas and views, all of which were published. It is a valuable historical source for the study of women's studies and modern Chinese history.

Yujiro Murata, a professor at the University of Tokyo, founded the The Ladies Journal Research Society in 2000, along with a number of other colleagues interested in women's history from Japan, Taiwan, China, and Korea. The two main goals of the Society are to produce a general catalog of all seventeen volumes of the Magazine and to bring together scholars from all over the world to conduct studies based on the magazine. With the assistance of the Institute of Modern History of Academia Sinica in Taiwan, the magazine was made into an online repository, which is stored on the Institute’s “Modern History Databases” website, and can be accessed by the public.

Link to the database: https://mhdb.mh.sinica.edu.tw/fnzz/index.php. Thanks to the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, for authorizing the CUA to repost.

Book

The Falun Gong Phenomenon

This book is a collection of several long articles and commentaries by Hu Ping on Falun Gong and the persecution and repression against Falun Gong practitioners. From an independent perspective, this book responds to a series of unfair criticisms and stigmatization of Falun Gong by the Chinese authorities and the public, calling on society to fight for the basic rights of Falun Gong practitioners who have been persecuted.

Book

On Freedom of Speech

“On Freedom of Speech” is a treatise by Hu Ping. It was first published in 1979. A revised version was published in 1980, when Hu ran for local elections at Peking University. The treatise was later published in Hong Kong in 1981 and again in a Chinese journal in 1986. Multiple publishing houses in China made plans to distribute the treatise in book form, but China’s anti-liberalization campaign prevented the books from publishing.

“On Freedom of Speech” explains the significance of freedom of speech, refutes misunderstandings and misinterpretations of freedom of speech, and proposes ways to achieve freedom of speech in China.

This document, provided by the author, also includes the content of the symposium held after the publication of “On Freedom of Speech” in 1986, as well as the preface written by the author in 2009 for the Japanese translation of this treatise.

Database

Modern Women’s Biographies Database

The Modern Women’s Biographies Database is part of the Modern History Digital Database of the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. The goal of the database is to create biographical information on women in modern China, in order to counter the dominance of biographies of male figures in modern China history. The database includes biographies of 1,848 women in modern China, a few of whom were not Chinese but were included because they taught at universities in China or Taiwan.

In addition to browsing and searching for biographies, the database provides two additional functions: 1. “Biography Connections”: users can select multiple biographies to generate a map displaying social connections among selected figures; 2. “Place of Origin Map”: a map presenting the places of origin and eras of the figures, and users can click the markers on the map to read the biographies of the figures. By visualizing the biographical information, users can have an overview of the organizational networks of modern women's groups, as well as the development of women's discourse.

Link to the database: https://mhdb.mh.sinica.edu.tw/women_bio/index.php. Thanks to the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, for authorizing the CUA to repost.

Database

Modern Women Journals Database

This database is part of the “Modern History Databases,” operated by the Institute of Modern History of Academia Sinica in Taiwan. The "Women and Gender History Research Group" of the Institute endeavors to collect, digitize and categorize related books and journals from libraries worldwide, and established the Modern Women Journals Database, which consists of 214 journals and 110,000 individual items. The database has been made available for public use since 2015.

In 1919 and the years that followed, women’s movement in China was on the rise, and as a result, many women's magazines appeared, a lot of which were run by women. Most of the journals collected in this repository were published between 1907-1949, with some published after 1949; there are comprehensive publications, as well as those focusing particularly on women's movements, family, health, employment, etc.; nearly a quarter of the publications were published in Shanghai, followed by Beijing, Guangzhou, and Nanjing. As can be seen from the Database, most of these journals have a relatively short duration, ranging from one to five years. Through this database, readers can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the history of women and women’s movements in modern China.

In addition to browsing journals and searching the database, users can also conduct author research and journal analysis. Under the author research section, users can read author biographies, as well as see the number of articles written by a particular author, and a map displaying their family and social relations. Under the journal research section, users can generate maps by keywords, eras, and article categories, which can provide more multi-dimensional information about a specific era or topic.

Link to the database:https://mhdb.mh.sinica.edu.tw/magazine/web/acwp_index.php. Thanks to the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, for authorizing the CUA to repost.